The story of Albert Milsted and Mary Ann Worthington is a tangled one, woven with tragedy, survival, and the stark realities of Victorian marriage and social expectations. What may seem unusual—an 18-year-old marrying a widow 14 years his senior, only for their union to dissolve within a few years—was not unheard of in the 19th century. However, understanding their choices requires looking beyond the bare facts and into the societal pressures, legal constraints, and financial motivations that governed relationships in Victorian Britain.

Marriage in the Victorian Era: Love or Survival?

Modern readers often think of marriage as a union of love, but in the Victorian era, marriage was as much about financial security and social survival as it was about personal attachment. Women, in particular, were at a distinct disadvantage. They had few legal rights, especially in regard to property ownership and business dealings.

For a woman like Mary Ann, twice widowed by the time of her marriage to Albert, remarriage would have been both a practical and necessary step. Running a business alone as a woman was difficult, and although widows had more legal freedom than unmarried women, they were still subject to strict social scrutiny. Marrying a much younger man may have raised eyebrows, but it also provided her with an able-bodied partner who could help manage her affairs.

For Albert, the marriage may have seemed like a logical step at the time. He had already been working at The Old Castle before the fire and was familiar with the publican trade. The marriage may have given him a stable footing in an industry that could offer economic security.

A Marriage That Didn’t Last

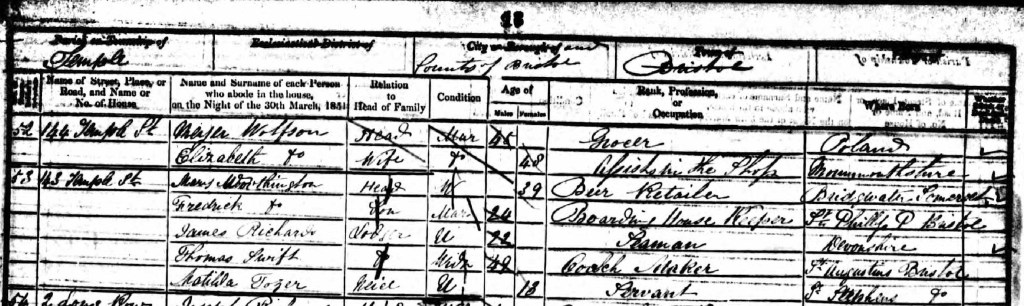

By 1851, Mary Ann had reverted to using her former married name and referred to herself as a widow, even though Albert was still alive. Why? Divorce was incredibly rare and expensive at this time. It was not a simple matter of “separating”—legal divorce required an act of Parliament until 1857 and was almost impossible for working-class people.

Instead, many Victorian couples simply went their separate ways and reinvented themselves, especially if there were no children from the marriage. A woman calling herself a widow was a socially acceptable way of moving on without facing shame or legal complications.

Bigamy: A Common Victorian Secret

Mary Ann did not stop with simply calling herself a widow. When she remarried in 1856, she listed herself as “Mary Ann Milstead, widow”, even though Albert was still alive. This means that her marriage to Thomas Swift was technically bigamous, though this was far from unusual in the Victorian era.

Bigamy was a crime, but prosecutions were rare unless the deception led to a financial scandal. Many people, especially working-class men and women, simply remarried without legally ending previous relationships because obtaining a divorce was beyond their means.

Even more striking is that Thomas Swift had also been previously married, but in his case, it seems his first wife may have passed away by the time of his marriage to Mary Ann. Still, both parties had complicated pasts, and by the time they wed, Mary Ann had likely learned how to adapt and survive in a world where a woman alone had few options.

Mary Ann’s Final Years: A Life of Hardship

Sadly, Mary Ann’s life did not take a turn for the better after her marriage to Thomas Swift. He died of cancer within a few months of their wedding, and Mary Ann herself died in early 1857 at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, having suffered from bronchitis and pleuropneumonia.

Her final years had been spent moving from one pub to another, frequently changing addresses, and seemingly trying to keep herself afloat in a difficult world. Her marriages, though perhaps strategic, did not bring long-term security.

Albert’s Life Beyond Mary Ann

Unlike Mary Ann, Albert’s life did not end in struggle and tragedy. He reappears in other records, forging his own path away from Mary Ann . He went on to reinvent himself, something that seemed to be a recurring theme in his life.

The contrast between their fates is striking: while Mary Ann relied on marriage to survive, Albert had the ability to leave and build a new life. This starkly reflects the gendered reality of Victorian society, where men had far more freedom to move on without consequence, while women were often trapped by their social status and financial limitations.

What Can We Learn from Mary Ann and Albert’s Story?

Their story is one of pragmatism, survival, and reinvention. In modern times, their choices might seem strange, even morally ambiguous, but within the context of their era, they were doing what they had to do to navigate the rigid structures of Victorian society.

Mary Ann’s series of marriages were likely not about romance but about ensuring stability in an unforgiving world. Albert, on the other hand, had the freedom to walk away and redefine himself, a privilege not afforded to many women of the time.

Their story invites us to look beyond the black-and-white morality that often colours discussions of past relationships. Rather than viewing them through a modern lens of right and wrong, we can instead appreciate the difficult choices they had to make and the hard realities they faced.

Albert Milsted may have moved on to a new chapter, but Mary Ann’s story reminds us of the challenges Victorian women endured—and the quiet resilience they displayed in the face of them.

Leave a comment