Robert Milsted’s Move to Bristol and Hat-Making Trade

Sometime before 1820, Robert Milsted moved from Cornwall to Bristol and found employment as a hat maker. Wearing a cap or hat was an essential feature of 19th-century etiquette, indicating social and economic class as well as marital status. For instance, a man wearing a top hat was seen as well-to-do and respectable.

Between 1830 and his death, Robert’s occupation is found in directories, census records, and newspaper advertisements listed as cloth cap maker, leather hat maker, fur cap maker, and furrier. His wife, Elizabeth, is often listed as a bonnet maker or milliner. Millinery was considered a respectable occupation for a woman, allowing her to work from home while raising a family.

Until the trade died out in the 1870s, hat making in Bristol and its surrounding villages was a significant industry, though it left no major architectural marks on the city. Robert likely operated a “cottage industry” hat-making business from his home, relying on fur imports through Bristol’s ports.

Materials and Working Conditions

Robert and Elizabeth used materials such as straw, card, leather, furs (e.g. beaver and rabbit), velvet, silk, satin, crepe, muslin, and cloth for their craft. They probably worked long hours each day in rooms with poor ventilation and lighting, leading to issues like eyestrain and digestive problems from prolonged sitting.

One occupational hazard was “mad hatter” disease, caused by chronic mercury poisoning. During a process called carroting, hatters exposed themselves to mercuric nitrate vapors, leading to symptoms such as depression, irritability, memory loss, delirium, headaches, tremors, and an irregular heartbeat.

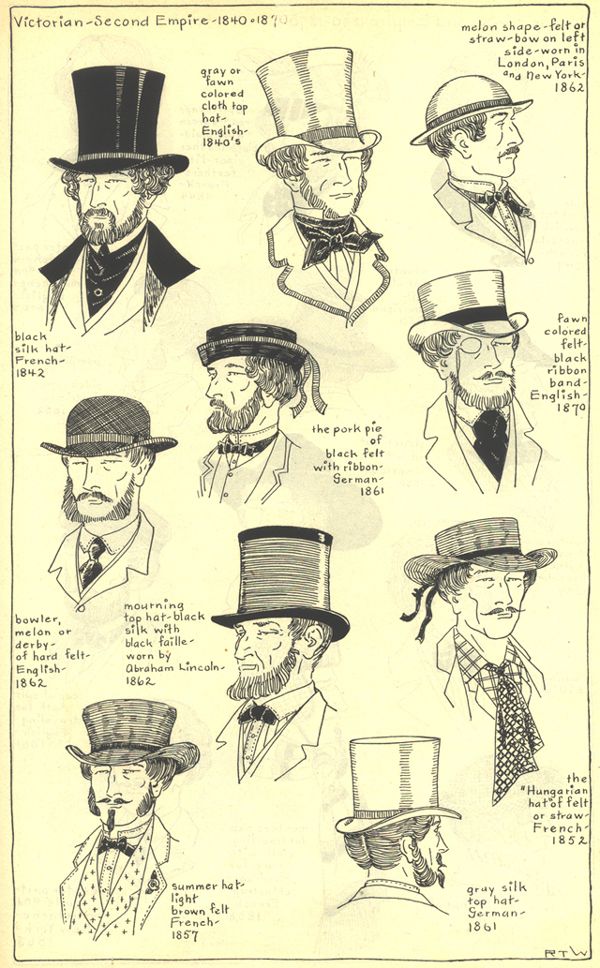

The Importance of Hats in 19th-Century Fashion

Fashion in hats changed more quickly than clothing; while dresses were expected to last eight to ten years, people planned to buy a new hat annually. Women wore linen caps with lace frills indoors and large bonnets outdoors to shade their faces. Hats also helped keep intricate hairstyles in place.

Men were always expected to wear a hat in public but remove it indoors. Top hats were standard for men of high social and economic status, while others wore them on formal occasions. Other popular Victorian men’s hats included the wide-brimmed “wide-awake” hats and the “porkpie” hat.

Robert and Elizabeth Milsted’s Family

There is no recorded marriage for Robert and Elizabeth, nor a maiden name for Elizabeth. Census records indicate that she was born in Brockweir, a village on the England-Wales border in the Forest of Dean.

Baptism records for Bristol suggest they had six children: Matilda (1822), Emily (1825), Robert (1825), Albert (1826), Fanny (1832), Lucy (1835), and Ellen (1838). During this time, King George IV headed the British government, and the 1820s were a relatively peaceful decade following the Napoleonic Wars. Many repressive laws were repealed, but the Corn Laws kept food prices high.

Legal Troubles of Robert Milsted’s Son

There are no further UK records for Matilda, Emily, and Robert, but a young Robert Milsted appears in two newspaper articles:

Incident in Cardiff (1841)

In January 1841, Robert Milsted and William Thomas were charged with damaging a house in St. Mary Street, Cardiff. The police arrested them at 2 AM, and they were ordered to pay damages and costs, as well as bound to keep the peace for a year. (Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, Glamorgan, Monmouth, and Brecon Gazette, 30 January 1841).

Trial in Bristol (1842)

In October 1842, Robert Milsted was convicted of stealing a hen from Robert Wayts. A policeman caught him in the act with a black-and-white mask concealed in his neckcloth. Found guilty, Robert was sentenced to three months of hard labour. (Bristol Times and Mirror, 29 October 1842).

Crime and Punishment in Victorian Bristol

The England & Wales Criminal Registers show that Robert’s trial took place on 22 October 1842, alongside 87 others. Most crimes were for larceny (burglary), with sentences ranging from a few weeks to six months of hard labour. Some prisoners were sentenced to “2 months and whipped.”

Victorian society believed hard labour would instill discipline, remove idle temptations, and provide cheap labour. At Bristol New Gaol, prisoners walked on a treadmill to draw up water, but poor ventilation and hygiene led to rapidly deteriorating conditions.

The Milsted Family in St James, Bristol

The Milsted family lived in the densely populated St James area of Bristol from at least 1830 to 1844. In 1841, the population numbered 10,555, having risen from 7,307 in 1801 and peaking at 10,658 in 1851 before declining.

Bristol’s economy relied on its port, canal waterways, and rail connections, though the city declined after the abolition of slavery in 1807. Competition from other docks and emerging northern cities also contributed to its downturn.

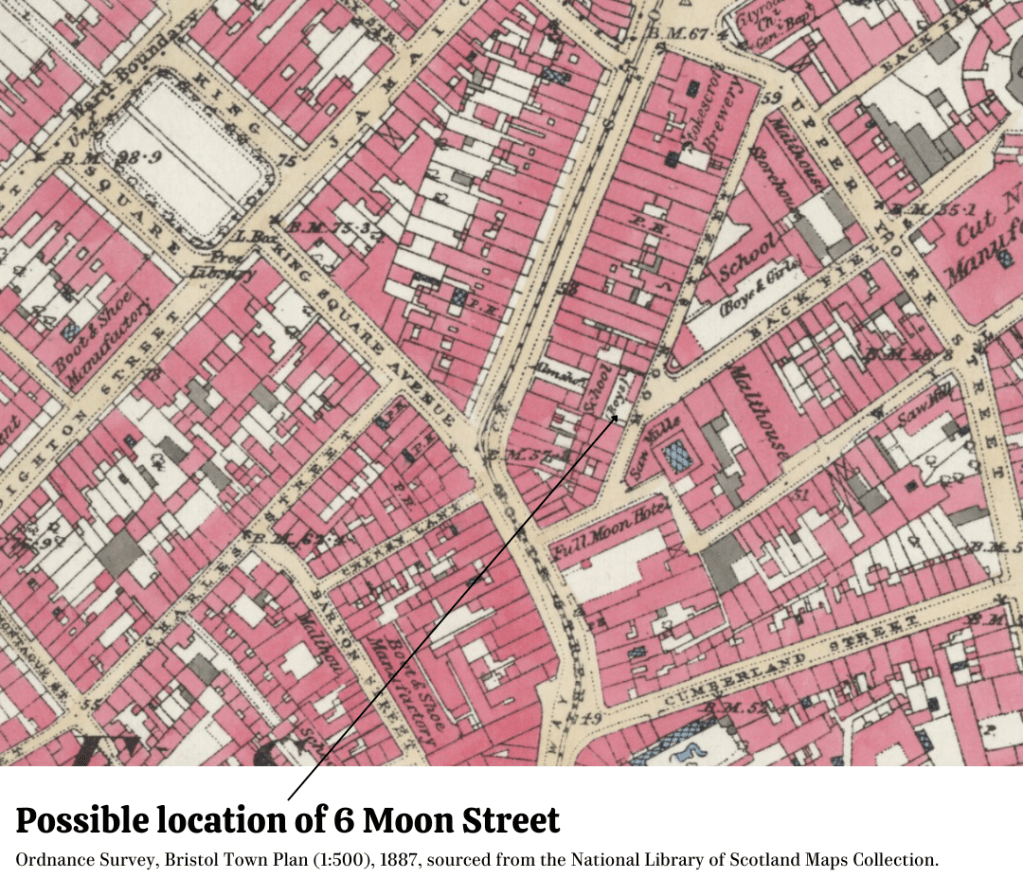

Robert Milsted’s Business in Moon Street

Pigot’s Directory of Gloucestershire (1830) lists Robert’s business at 6 Moon Street. However, a sale of this property in 1835 forced him to move. A July 1835 auction notice described the premises as part of a larger sale in Stoke’s Croft. Other businesses on Moon Street included a carpenter, builder, stonemason, brightsmith, bell hanger, and boot and shoe maker.

Moon Street, adjacent to Stokes Croft, became a busy shopping area in the mid-1800s, with residents running businesses from their homes. Today, the area is known for its association with Banksy’s The Mild Mild West mural, though it has long been a crime hotspot. Many buildings were destroyed by WWII bombings, though the Full Moon Hotel remains a 19th-century landmark.

Stokes Croft and Backfields

Backfields, behind Stokes Croft, was once an open space used for visiting circuses. A permanent circular building was erected in 1837, later known as the “Palace of Varieties,” hosting prize fights and music hall performances until the Salvation Army took over in 1880. A fire destroyed it in 1895.

The Bear Pit, south of Moon Street, was once the site of St James’s Fair, one of Europe’s largest annual fairs, running from 1238 until 1837, when authorities banned it due to excessive drunkenness and disorder.

Leave a comment